What is the Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PLC)?

There are several ligaments that are vital for the stability of the knee joint. One of these is the Posterior Collateral Ligament (PCL).

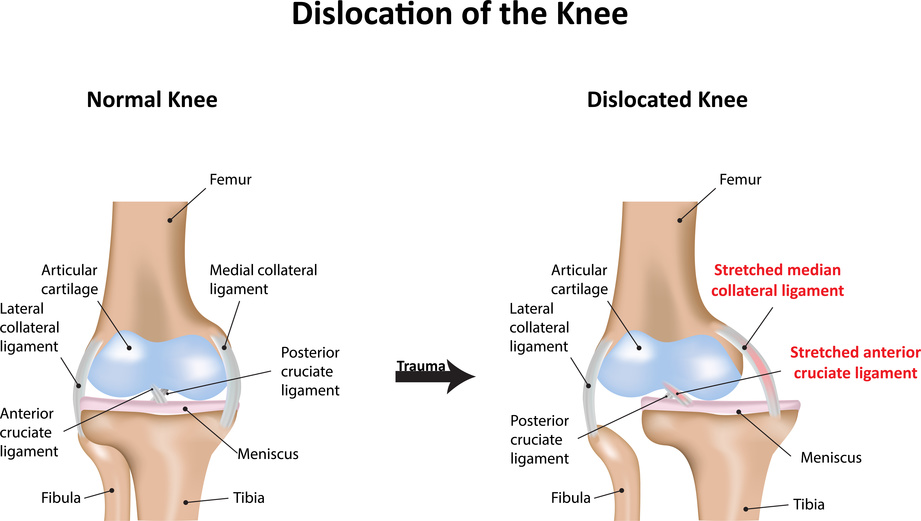

The PCL helps to stop the tibia (shin bone) from moving backward in the knee joint. It is situated within the joint, joining the front lower position of the thigh bone above the distal femur to the rear of the upper position of the shin bone below the proximal tibia.

SUMMARY

In this article you will learn what the PCL ligament is, the signs, symptoms and how to diagnose a torn PCL. You will learn how surgery is performed and how you can both prevent and recover from an PCL surgery.

A ruptured PCL is one of the less common knee ligament injuries. This ligament is stronger and wider than other ligaments associated with the knee, making it less vulnerable to damage.

The main function of the PCL is to stop posterior translation of the tibia during flexion. It also acts as a secondary stabiliser for varus and rotation stability.

The following video shows how to test for an injury of the PCL as well as the structure of the knee and the position of the posterior cruciate ligament relative to other knee ligaments.

Causes of a torn PCL

Approximately 20% of knee ligament injuries include PCL tears. Like other forms of ligament damage, a torn PCL often results following a specific movement that puts excessive strain on the ligament.

There are several movements which can damage the PCL, including knee twisting, knee hyperextension, and backward motion of the tibia on the femur. These abnormal movements extend the ligament beyond its normal range, causing damage.

PCL damage most frequently occurs during sporting activities that involve contact or rapid direction changes. Most commonly a tear develops through a hyperextension force or a direct impact to the front of the shin while the knee is bent. Landing awkwardly may also damage the PCL. In some cases, repetitive straining of the ligament will also cause tearing.

Research shows that that sport injuries account for 37% of PCL tears, while 56% are a result of trauma1.

Signs, symptoms and diagnosis of a torn PLC

At the time of the injury a tearing or snapping sound may be heard. If the injury isn’t significant, patients can often continue activity. This is usually followed by swelling, pain, and stiffness after a period of resting. The discomfort is generally localised to deep within the knee or towards the back of the knee.

If the PCL is completely ruptured, the pain can be very severe. The knee joint often feels misplaced and is unstable. The severity of swelling will vary between patients and in some cases it is not possible to bear weight. Stiffness and bruising occur, also limiting movement. It’s not uncommon for recurrent instability of the knee following a serious PCL tear.

A PCL injury can be diagnosed by a doctor and in some cases will need detailed examination through x-rays and other scanning procedures.

The classification of PCL injuries is as follows:

Other ligaments may also be damaged along with the PCL, increasing recovery time and the likelihood of requiring surgery.

Treatment options for a torn MCL

The treatment for a PCL will depend on the severity of the injury. For minor tears the PRICE approach can be beneficial:

Pain relief medication may also be necessary. Usually Grade 1 and 2 PCL injuries will recover well following this approach. In some cases physical therapy is necessary to aid rehabilitation. This may include a period of time on crutches before returning full weight to the knee. A knee brace may also be required.

Observational studies indicate that isolated PCL injuries can be conservatively treated with good prognosis. Shelbourne and colleagues isolated grade 1 and 2 PCL injuries using bracing for a period of six weeks. Nineteen of the twenty-one patients showed healing under MRI scanning and improved stability.

For bracing to be effective, it should be applied within the initial week of sustaining the injury2. Specific exercises and muscle strengthening techniques are also beneficial. Usually patients can return to their normal activity within two to eight weeks.

In some cases surgery will be necessary. This usually applies to patients that have injuries involving multiple ligaments, or when pieces of bone have broken off and become loose. If the PCL is persistently loose and causes ongoing knee instability surgery may be required.

PCL surgery typically involves replacing the ligament with a tendon from some other part of the body, rather than trying to stitch it together. This procedure may be performed as open surgery or less invasive arthroscopy. Rehabilitation takes approximately six to twelve months, in some cases longer.

It is difficult to prevent PCL injuries. Maintaining good flexibility and strength can help, as well as applying the correct techniques within chosen athletic activities. Function knee braces can help to lower the risk of recurring PCL injuries.

For more information about protecting the knee from ligament injury, read our article on torn medial collateral ligament (MCL).

MCL surgery

Surgical reconstruction is often recommended when patients have multiple knee ligament injuries, isolated grade 3 injuries, or chronic instability associated with the posterior cruciate ligament. The procedure replaces the torn PCL with a single bundle/strand of tissues or a double bundle (two strands).

These grafts may be an autograph (from the patient’s own body), such as a patellar tendon, or an allograft from a cadaver. At this stage, comparisons between a PCL autograph versus PCL allograft have not shown any significant differences in outcomes.

During the surgery, the grafts are positioned and anchored in tunnels that are carefully drilled in the tibia and femur. Radiographic landmarks are used as guidelines for the PCL anatomic reconstruction in both postoperative and intraoperative settings in single and double-bundle reconstructions3.

There have been a number of studies assessing the effectiveness of both single and double-bundle PCL reconstructions. Some studies indicate that a double-bundle PCL reconstruction can restore the biomechanics of an intact knee more closely than a single-bundle reconstruction45.

However, these laboratory and cadaveric study results are yet to be confirmed with clinical studies. Other research suggests that both single and double-bundle reconstructions have similar outcomes67.

Still a controversial subject, more research is necessary to confirm which surgical approach offers the best results.

Prevention and recovery

Education

Knowing how to correctly land or fall can assist in the prevention of PCL injuries. For example, falling sideways or forward rather than backwards can help to reduce the stress on knee joints. People participating in sports such as skiing, basketball, football and soccer should practice landing/falling correctly as part of their training.

Stretching

Muscles and ligaments should be prepared for aerobic activity by engaging in proper warm-ups. This helps to minimise any shock from sudden motion. Three to five minutes of light aerobic exercise is usually sufficient. Stretching the muscles around the knee after exercise is also important for preventing tightening of the PCL during recovery.

Strengthening

Maintaining strong muscles around the ligaments and knee joint can help to reduce the strain on the PCL. Strong quadriceps muscles are particularly beneficial. Located above the knee, these muscles are used in running and can be strengthened with squats and lunges.

Rest

The PCL can wear out and be stretched over time. Thus, it’s important to allow the body time to recover. Alternating between high and low-impact activities can help to minimise the strain on the knee.

Nutrients Supporting Ligament Recovery

One way patients can help to accelerate the healing process is to ensure that their diet is enriched with certain vitamins, minerals, trace elements, and antioxidants. Vitamin C is a key nutrient that helps to boost antioxidant activity and protect the tissues while healing.

Working well together with omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin C is an important inflammation mediator and can increase mobility and reduce pain. Trace elements such as copper and zinc also lower oxidative stress and increase circulation to speed up the repair process.

A diet rich with fresh vegetables and fruit, combined with high quality protein is recommended for anyone suffering from any tissue damage. Certain supplements may also be helpful.

Buyer’s Guide: Supplements for Ligament Recovery

Bibliography

- Petrigliano F. and McAllister D. (2006). Isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee. Sports Med Arthrosc, Volume 14, Issue 4, (pp. 206-212)

- Shelbourne, K. et. al. (1999). Magnetic resonance imaging of posterior cruciate ligament injuries: assessment of healing. Am J Knee Surg. Volume 12, Issue 4, (pp. 209-13).

- Johannsen, A. et.al. (2012). Radiographic landmarks for tunnel positioning in posterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. American Journal of Sports Medicine, published online before print November 9, 2012

- Harner, C. et.al. (2000). Biomechanical analysis of a double-posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. American Journal of Sports Medicine. Volume 28, Issue 2, (pp. 144-51)

- Markolf, K. (2010). Single versus double-bundle posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction – Effects of femoral tunnel separation. American Journal of Sports Medicine. Volume 38, Issue 6, (pp. 1141-46)

- Wang, C. et.al. (2004). Arthroscopic single- versus double-bundle posterior cruciate ligament reconstructions using hamstring autograft. Injury, Volume 35, Issue 12, (pp. 1293-9)

- Voos, J. et.al. (2012). Posterior cruciate ligament: Anatomy, biomechanics, and outcomes. American Journal of Sports Medicine. Volume 40, Issue 1, (pp. 222-31)